The Aeta boy held up a baby python as big as his arm. He was one of seven kids, with hair like wiry birds' nests, who rushed towards us as we stepped off the jeep. We were at Patal Pinto, the starting line on the route to the crater lake campsite of Mt. Pinatubo.

The Aeta boy held up a baby python as big as his arm. He was one of seven kids, with hair like wiry birds' nests, who rushed towards us as we stepped off the jeep. We were at Patal Pinto, the starting line on the route to the crater lake campsite of Mt. Pinatubo.A girl wanted to show us the parrot that she gently cupped in her hands. Another boy had a mongoose-like rodent that darted from his wrist to his neck, occasionally straining forward to sniff the breeze surrounding the backpacked newcomers. Wildlife central it sure was.

Their parents, seeing our interest in the animals, tried to start a bidding. "Two hundred pesos," one said. A guy in our group visibly brightened. He knew the python's market price was by the thousands, and he had an empty aquarium at home where he used to keep a garter snake before it somehow got misplaced around the house.

The women tried dissuading Snake Boy. We were not about to support wildlife trade in any scale. Also, we didn't relish sharing the ride home with anything that could slither away. "What are you going to feed him?" was the challenge. "White mice and chicks, of course" was the response. More shrieks.

Aeta families poured out of the makeshift shed on the rock platform. Some were waiting for the random jeep bringing fresh produce so they could hitch a ride to the market. Some just wanted a peek at the newest batch of pallid city folk who would actually pay for the privilege of walking for five to eight hours through sandy, scorching terrain.

Aeta guide Popoy rounded us up and then set out on jaunty steps. For someone relaxed and smiling, he covered ground fast. We hurried after him. Our sandals sank an inch into the sand, evoking shoreline images. The sun had the day-at-the-beach quality, and well, we could have used some goggles to keep the sand grains from irritating our eyes. But thinking of bodies of water where it couldn't possibly be was needless taunting. Or so we said until we came across our first rivulet. It ran across the sand like splayed fingers. The sight of it was an initial surprise. To find the trail punctuated with spring water (ground spurts, trickles from a rock wall, tiny falls) was soothing to the eye, and a hint of the large crater lake waiting for us at the campsite. Several times, we had to wade through. Water-logged hiking boots would only weigh us down so we strapped on rubber sandals. The water was gurgling warm to our toes. When we stepped out, our feet were espasol with the sand coat. I could only imagine what trekking hereabouts must be like in torrential rain. The lahar would suck on the boot like a nursing baby.

We met another group of foreign tourists on their way back. They were in shorts and tank tops. In contrast, my group wore bandannas, shades, arm protectors, tights, and a smearing of sun block. The tourists carried light rucksacks. We were armed to the teeth. Why? Two words. Cooking showdown. Dinner in the mountains always is with this group. (Anyone else can make do with canned goods if the thought of lugging stoves and pots do not exactly bring a spring to your step.) We felt less sheepish when we found out the tourists employed porters who had, among their load, an inflatable raft with oars.

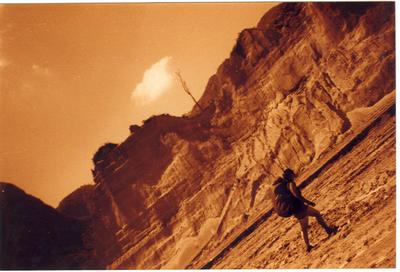

We stopped for lunch and then proceeded along even stranger terrain. Someone described it as an alien planet. The artist's palette is pared down to the black, white, and gray. A series of peaks, like wave crests, needled the air. Loose sand dribbled down the side of mountains collecting like half an hourglass below. Basketball-sized rocks were melded together in a way that, my friend imagines, would stir a garden landscaper's imagination. Some formations looked like the ruins of an amphitheater or a labyrinth. Boulders were strewn across the ground like a checker game played by giants. The canyons sat solid.

We stopped for lunch and then proceeded along even stranger terrain. Someone described it as an alien planet. The artist's palette is pared down to the black, white, and gray. A series of peaks, like wave crests, needled the air. Loose sand dribbled down the side of mountains collecting like half an hourglass below. Basketball-sized rocks were melded together in a way that, my friend imagines, would stir a garden landscaper's imagination. Some formations looked like the ruins of an amphitheater or a labyrinth. Boulders were strewn across the ground like a checker game played by giants. The canyons sat solid.No one made small talk, and that's saying a lot for our group. This felt like sacred space and we were engaged in a kind of body prayer. We marched into our own private musings. About how, for example, movement even as basic as putting one foot after another opened the body to childlike joy. Hiking for long hours taught me to take pleasure in the moment-by-moment experience. I also couldn't help mulling over the enormous amount of energy that the earth released to change this part of her face. And she hasn't settled on a look yet. One companion had been here thrice and each time the route looked different. Wind and rain still shifted sand and stone. The ancients believed that "the earth bursts forth because it is trying to grow. It is trying to return to paradise."

Guide Popoy said some of his Aeta relatives were buried where we trudged. There used to be thriving barrios here. Now there was only wide expanse. Our guy with the third eye (there's always one in every hiking group) said souls still wandered across the landscape.

Just when we thought we were never going to stop hiking, we finally stood at the big drop overlooking the crater lake. Descending required tricky footwork. Rocks kept coming loose in our hands or dropping from under our feet. Nevertheless, we picked up our pace because the light was fading fast.

We reached the campsite barely minutes before it got dark. We pitched our tents, had a fiesta of a meal, admired the stars, and, for the first time in our group history, actually cut short our socials for sleep. We still can't get over that one.

I woke up the next day to the sound of someone swimming in the sulphuric lake. After a quick breakfast and not-so-quick photo shoot, we trekked back. We made it in five hours, with visions of ice-cold halo-halo dancing in our heads. Casualty check yielded a torn shoe, a pair of sandals with both soles ripped off, another pair of sandals sanded thin, and one pair of involuntary buckling knees. We also turned two shades darker, some getting their tan in stripes (blame straps and bandannas). One last lesson for us: Our jeep didn't show up. Luckily, another jeep docked in to deliver sacks of rice. We sent our prettiest to do the haggling. Done deal.

Just before we boarded, an Aeta handed a slow-wriggling sack to our companion. This was a boy's pet, my friend whispered. Feeling our eyes on him, the Aeta made a ceremony of calling his son and awarding him the two P100 bills. Even with the departing jeep's dust trail, bewilderment was evident on the boy's face as he stared at the paper in his hands for what seemed a long time.

0 left a footprint:

Post a Comment